If mankind is, as has been claimed since ancient days, a species driven by the narrow passions of self interest, what holds human society together as one cohesive whole? How can a community of egoists, each devoted to nothing but his or her own ambition, thrive? Or for that matter, long exist?

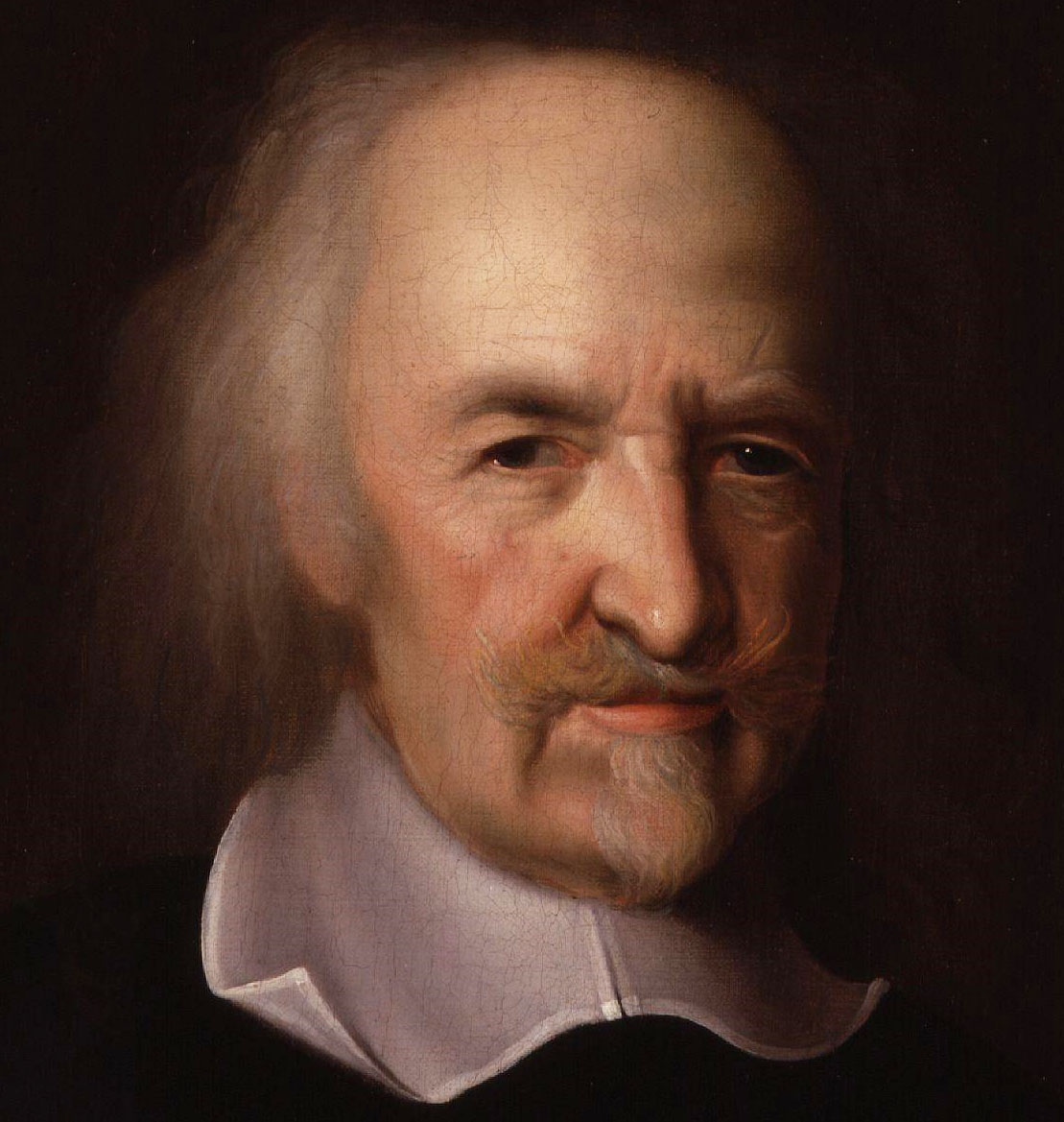

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury thought he knew the answer.

Image Source.

Hobbes is famous for his dismal view of the human condition. But contrary to the way he is often portrayed, Hobbes did not think man was an inherently evil being, defiled by sin or defined by vileness ingrained in his nature. He preferred instead to dispense with all ideas of good and evil altogether, claiming “these words of good, evil, and contemptible, are ever used with relation to the person that useth them, there being nothing simply and absolutely so; nor any common rule of good and evil, to be taken from the nature of the objects themselves; but from the person of the man.”1 Only a superior power, “an arbitrator of judge, whom men disagreeing shall by consent set up” might have the coercive force to make one meaning of right the meaning used by all. Absent such a “common power”, the world is left in a condition that Hobbes famously described as “war of every man against every man” where they can be no right, no law, no justice, and “no propriety, no dominion, no ‘mine’ and ‘thine’ distinct, but only that to be every man’s that he can get, and for so long as he can keep it.“2

This description of the wretched State of Nature is familiar to most who have studied in the human sciences at any length. Also well known is Hobbes’s solution to the challenge posed by anarchy:

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, or The Matter, Form, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiastical and Civil (1651), Book I, Chapter VI.

ibid. Book I, Chapter XIII.

[Those in this state will] appoint one man, or assembly of men, to bear their person; and every one to own and acknowledge himself to be author of whatsoever he that so beareth their person shall act, or cause to be acted, in those things which concern the common peace and safety; and therein to submit their wills, every one to his will, and their judgements to his judgement. This is more than consent, or concord; it is a real unity of them all in one and the same person, made by covenant of every man with every man, in such manner as if every man should say to every man: I authorise and give up my right of governing myself to this man, or to this assembly of men, on this condition; that thou give up, thy right to him, and authorise all his actions in like manner. This done, the multitude so united in one person is called a COMMONWEALTH; in Latin, CIVITAS. 3

Hobbes, Leviathan, Book II, Chapter XVII.

What is most striking in Hobbes’ vision of this State of Nature and the path by which humanity escapes it is his complete dismissal of any form of cooperation before sovereign authority is established. Neither love nor religious zeal holds sway in the world Hobbes describes, and he has no more use for ties of blood or oaths of brotherhood than he does for the words right and wrong. He does concede that if faced with large enough of an outside threat fear may drive many “small families” to band together in one body for defense. However, the solidarity created by an attack or invasion is ephemeral–once the threat fades away so will the peace. “When there is no common enemy, they make war upon each other for their particular interests” just as before. 4 Hobbes allows for either a society dominated by a sovereign state or for a loose collection of isolated individuals pursuing private aims.

Hobbes’ dichotomy is not presented merely as a thought experiment, but as a description of how human society actually works. Herein lies Hobbes’ greatest fault. Today we know a great deal about the inner workings of non-state societies, and they are not as Hobbes described them. The man without a state is not a man without a place; he is almost always part of a village, a tribe, a band, or a large extended family. He has friends, compatriots, and fellows that he trusts and is willing to sacrifice for. His behavior is constrained by the customs and mores of his community; he shares with this community ideas of right and wrong and is often bound quite strictly by the oaths he makes. He does cooperate with others. When he and his fellows have been mobilized in great enough numbers their strength has often shattered the more civilized societies arrayed before them.

The social contract of Hobbes’ imagination was premised on a flawed State of Nature. The truth is that there never has been a time when men and women lived without ties of kin and community to guide their deeds and restrain their excess, and thus there never could be a time when atomized individuals gathered together to surrender their liberty to a sovereign power. Hobbes mistake is understandable; both he and the social contract theorists that followed in his footsteps (as well as the Chinese philosophers who proposed something close to a state of nature several thousand years earlier) lived in an age where Leviathan was not only ascendent but long established. They were centuries removed from societies that thrived and conquered without a state. 5

To answer the riddle of how individuals “continually in competition for honour and dignity” could form cohesive communities without a “a visible power to keep them in awe, and tie them by fear of punishment to the performance of their covenants,” 6 or why such communities might eventually create a “common power” nonetheless, we must turn to those observers of mankind more familiar with lives spent outside the confines of the state. Many worthies have attempted to address this question since Hobbes’ day, but there is only one observer of human affairs who can claim to have solved the matter before Hobbes ever put pen to paper. Centuries before Hobbes’s birth he scribbled away, explaining to all who would hear that there was one aspect of humanity that explained not only how barbarians could live proudly without commonwealth and the origin of the kingly authority that ruled civilized climes, but also the rise and fall of peoples, kingdoms, and entire civilizations across the entirety of human history. He would call this asabiyah.

ibid

Hobbes defenders try to downplay this err by claiming the State of Nature was but a thought experiment. How they explain away Hobbes’ specific reference to the peoples of the American wildness living in just such a state, and also the sorry lives of all caught in a civil war, is beyond me.

For the Chinese philosophers, see Mozi 11; Book of Lord Shang 7. There is also a passage in the Huainanzi of a similar nature; I ask readers to forgive me for not having time to pour through its 1,000 pages to try and find it right now.

Hobbes, Leviathan, Book II, Chapter XVII.

Bronze bust commissioned by the Tunisian Community Center

Image Source.

Ibn Khaldun was born in 1332 in Tunis, then one of the grander cities of the Islamic world. He became a hafiz at a very young age, received ijazah in the hadith, sharia, and fiqh, and memorized volumes of Arabic poetry and prose as a young man. In addition to this classical Islamic education, Khaldun was given the opportunity to study logic, mathematics, and philosophy–including Greek philosophy–before he began his official political career. The formative events of his life occurred there in the sands of North Africa, as Ibn Khaldun moved from one dynasty to the next, cannily jumping from one king’s court just before it fell to the sword of another. This life of wandering led him across the Maghreb and Al-Andalus, observing first hand the cycles of flourishing and failure that would form the centerpiece of his political philosophy. He would eventually retire to Cairo, remaining there until the end of his days, interrupted only by an assignment to act as Nasir-ad-Din Faraj‘s diplomatic envoy to Timur the lame. 7

Ibn Khaldun’s life work was a gigantic multi-volume history called the Book of lessons, Record of Beginnings and Events in the history of the Arabs and Berbers and their Powerful Contemporaries. As the title suggests, Khaldun wished to write a universal history that moved from the time of Adam to the dynasties he had seen rise and fall before his eyes. However, Khaldun is most famous today not for his history, but for the supplement he wrote to preface it. In this Muqaddimah (Arabic for “Introduction”) Ibn Khaldun set out to establish a new and “independent science” that would aid a historian trying to find the truth in the many conflicting accounts of the past. Such a science:

Both these biographical details and those reported later in the essay are taken from Allen Fromherz, Ibn Khaldun: Life and Times (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011) and Franz Rosenthal, Introduction to Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, trans. Franz Rosenthal (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1958), vol I, i-lxvvii.

has its own particular object – that is, human civilization and social organization. It also has its own particular problems – that is, explaining the conditions that attach themselves to the essence of civilization, one after another. 8

Ibn Khaldun, Muqaddimah, Vol I, p. 76

In other words, Ibn Khaldun sought nothing less than to discover and explain the basic laws and principles upon which all of human society operated. For his efforts Ibn Khaldun has been acclaimed in turn as the first economist, the first sociologist, and the first true social scientist of human history. In English translation his Muqaddimah is three hefty volumes in length.9 Its contents range from poetry to climatology. Libraries could be written analyzing this book without fully plumbing it depths. Alas, a library is beyond my capacity. I reserve myself to the less ambitious task of introducing one concept key to most of Ibn Khaldun’s wider work and detailing some of the ways Khaldun applied it. This concept is of course asabiyah.

The term asabiyah has been variously translated as “solidarity,” “group feeling,” “social cohesion,” and even “clannishness.” Ibn Khaldun did not invent the term, but he did retool it for his own purposes. The meaning he imparted to it is largely what it means today.

To introduce the idea of asabiyah I like to start in a place where the cold Hobbseian logic of fear and interest break down: the battleground. This example is not what Ibn Khaldun uses to explain the concept, but it does accord with his later outline of the principles that lead to victory or defeat. 10 War is an activity that requires extreme sacrifices from those called to wage it. Imagine if you will a Roman legion, Greek phalanx, or any kind of ancient army that required men to stand arrayed in line against a foe as terrible as themselves. How does a commander of such a force motivate his men to obey his commands despite the terror, tiredness, and sheer brutality to be found on the killing fields of war? The Legalists of ancient China thought great rewards for valor and dreadful punishments for cowardice or insubordination would be enough to command the devotion of the soldiery. Theirs was an attempt to align the private passions of the masses with the will of the state, and with this Hobbesian logic they hoped to throw conscripts and slaves into battle without needing to worry about loyalty or other soft emotions of the soul. 11 As the success of the Qin armies demonstrates, their methods had merit. But theirs was a strategy that worked best when the battle was easy and victory was certain. When victory is in doubt, when rewards may not be given, and death seems certain for both those who follow orders and those who shirk them, the Hobbesian approach falls apart. In such dire times the self interested soldier realizes that his personal interest would be better served by fleeing from the field of battle than staying to be sacrificed for the greater cause.

An army composed of men more concerned with their own appetites and advantage than the army’s fate is an army that, other things being equal, will be defeated. The force that conquers or defends ‘against all odds’ is a force imbued with a spirit of solidarity whose strength is more compelling than naked self interest could ever be. This spirit of sacrifice and common cause may be the fruit of patriotic fervor or revolutionary zeal, though often it is simply the sort of battleground loyalty that turns a group of strangers into “a band of brothers.” It is this feeling that compels the self interested man to lead the charge and hold fast the standard despite the seeming irrationality of his position. It is not an emotion that causes men to ignore or forget self interest so much as it is a virtue that causes them to identify their narrow passions with the greater cause. For as long as this conviction lasts, the soldier thus enraptured will believe sincerely that the army’s gains are his gains and that the army’s fate is his fate. Even in most desperate straits he will work with the strength and focus normally reserved for attaining private advantage, for in his mind the distinction between “self interest” and “group interest” will no longer be important.

The feeling and conviction that causes a man to think and act this way is what Ibn Khaldun called asabiyah.

I have introduced asabiyah as a passive element–something an army has or has not. Ibn Khaldun understood asabiyah in much more dynamic terms, as a variable that not only changed history but was changed by it. His theories, as I have noted above, were based on his experience and his study of politics in the Mahgreb, where Berber nomads often swept out the desert to conquer sedentary kingdoms, established themselves as rulers there, and were then in turn swept away by the next incursion from the wilds. Central to this cyclical vision of politics is the distinction Ibn Khaldun makes between Umran, or “civilization,” and Budawah, or “the Bedouins.” Ibn Khaldun used the term Budawah to describe not only nomadic tribes, but also sedentary rural people living far away from great population centers–in essence, any place where life was rough and there was no Leviathan to order relations between one man and another.

Far away from the Leviathan’s reach social organization devolves to the tribe and family. Appropriately, Ibn Khaldun introduces asabiyah first in familial terms:

More than five years ago I had the luck to find the 3-volume Rosenthal translation of the entire Muqaddimah in the library. I slogged through the whole thing (and then read the Issawi translation excerpts on top it) before the month was over. I copied down a lot of interesting passages into a ms word document so that I might use them later, and that is what I will be citing in this discussion. I cannot recheck the context for all these statements, as I am several thousand miles away from the library in question, but I believe they will serve for the purpose at hand. Unless stated otherwise, all quotations that follow are from volume I of Rosenthal’s translation.

Princeton University Press has since published an abridged (512 page) version of this same translation.

bn Khaldun, Muqaddimah, Vol II, 73-90. See esp. his comment on page 87:

What is the fact proven to make for superiority is the situation with regard to group feeling. If one side has a single group feeling comprising all, while the other side is made up of numerous different groups, and if both sides are approximately the same in numbers, then that side that has a single comprehensive group feeling is stronger than, and superior to, the side that is made up of several groups. These groups are likely to abandon each other, as it the case with separate individuals who have no group feeling at all, each group being in the same position as an individual.

For a particularly clear statement, see Book of Lord Shang, sec. 11.

“Their [the Bedouins] defense and protection are successful only if they are a closely knit group of common descent. This strengthens their stamina and makes them feared, since everybody’s affection for his family and his group is more important (than anything else). Compassion and affection for one’s blood relations and relatives exists in human nature as something God put into the hearts of men. It makes for mutual support and air, and increase the fear felt by the enemy.

…[Those without their own lineage] cannot live in the desert, because they would fall prey to any nation that might want to swallow them up.”12

Ibn Khaldun, Muqaddimah, Vol I, 25.

Mutual reliance and kinship among these clans will naturally lead to a strong asabiyah. But Ibn Khaldun also states there is nothing inherent in common descent itself that makes asabiyah possible. In the wilds families exist because if they did not then men would be soon be overwhelmed and destroyed by circumstance and danger. Feasibly other groups (for example, the tight-knit communities of ‘social bandits,’ which in places like China have routinely taken their asabiyah and transformed it into armies, kingdoms, and dynasties) could gender the same sense of loyalty if placed in similar circumstances. Thus Khaldun notes:

“The consequences of common descent, though natural, still are something imaginary. The real thing to bring about the feeling of close contact is social intercourse, friendly association, long familiarity, and the companionship that results from growing up together having the same wet nurse, and sharing the other circumstances of life and death. If close contact is established in such a manner, the result will be affection and cooperation.” 13

ibid., 374.

The simplest and clearest description of asabiyah’s requirements is given by Lenn Evan Goodman in his essay “Ibn Khaldun and Thucydides”:

“The tragic fact of history, however, which Ibn Khaldun insists on bringing before us, is that in politics whatever can be demanded will be demanded. Thus ‘asabiyya, whether in the nation or the tribe, becomes a matter of willingness to die.’ It is because this is so that nations and tribes, and the families, states or dynasties which rule them, have finite lifespans. Unless individuals are prepared to die for their group, the group itself will die.” 14

Lenn Evan Goodman, “Ibn Khaldun and Thucydides,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 92, no. 2 (1972), 260. This essay is by far the best commentary on Ibn Khaldun’s thought written in the English language. I strongly recommend it to everyone who can access it.

Goodman’s point is echoed by Ibn Khaldun’s definition of asabiyah:

This shows most clearly what asabiyah means. Asabiyah produces the ability to defend oneself, to protect oneself, and to press one’s claims. Whoever loses (asabiyah) is too weak to do any of these things (Ibn Khaldun, Muqaddimah, Vol II, 289).

These requirements start with the clan and by necessity define the clannish life. But asabiyah does not end there:

“Once asabiyah has established superiority over the people who share in that particular asabiyah, it will, by its very nature, seek superiority over people of other asabiyah unrelated to the first. If the one asabiyah is the equal of the other or is able to stave off its challenge, the competing people are even with and equal to each other. Each asabiyah maintains its own domain and people, as is the case with tribes and nations all over the Earth. However, if the one asabiyah overpowers the other and makes it subservient to itself, the two asabiyah enter into close contact, and the defeated asabiyah gives added power to the victorious one, which, as a result, sets it goal of domination and superiority higher than at first.”15

Ibn Khaldun, Muqaddimah, Vol I, 285.

Now Ibn Khaldun is never really too explicit on what exact mechanism allows one “asabiyah to overpower another.” He is quite empathetic that religion is not this mechanism, and goes to great lengths to point out how the early Arab conquests and the consolidation of the Arab tribes by Muhammad and the early Caliphs are anomalies that his theory can not explain. He views that period in human history as singular, a direct product of God’s will and interference, not the natural product of the laws God devised to regulate the universe.

In Ibn Khaldun’s thought, conquest itself seems to be the driving force behind the consolidation of two asabiyah into one. Once a weaker tribal group is defeated, its leaders removed and men of valor killed, pacified, or subsumed under a new organization so utterly that the ‘tit for tat’ vengeance schemes so common to nomadic society (which Ibn Khaldun sees as the root cause of war) are no longer possible, then their asabiyah can be swallowed up in the larger group’s. What is key here is that the other groups – after their initial defeat – are not coerced into having the same feeling of asabiyah as the main group. Asabiyah that must be coerced is not asabiyah at all (this is a theme Ibn Khaldun touches on often and we will return to it in more detail when we talk about why asabiyah declines in civilized states). Instead, those who have been allowed to join the conquering host slowly start to feel its asabiyah be subsumed as the two groups “enter into close contact,” sharing the same trials, foods, circumstances, and becoming acquainted with the others’ customs, but just as importantly, sharing the same set of incentives. Once the losers are are forced together with the winners, defeat for the main clan is defeat for all; glory for the main clan is glory for all; booty gained by the main clan’s conquests becomes booty to be shared with all. Once people from a subordinate group begin to feel like the rise and fall of their own fortunes is inextricably linked to the fate of the group that overpowered them then they become willing to sacrifice and die for the sake of this group, for it has become their group.

If one studies the formation of steppe confederacies in Inner Asia, such as the Xiongnu, Turks, Keraits, and the later Mongols (and to an extent Chinggis’ Empire, thought that one followed a slightly different path) it is not difficult to see this process unfold almost exactly as recounted.

.jpg)

Bedouin wedding series: Mounted Bedouins racing (c. 1910)

Image Source.

Though asabiyah has its beginnings in the world without a state, it does not stay in that world. As Ibn Khaldun describes it this is because men and women cannot collect in too large a mass without there being some form of hierarchy to coordinate their actions and leadership to resolve inner disputes. Give man a little power and he will strive for more; it is the nature of the leader of the moment to try and make his authority permanent–a type of authority that Ibn Khaldun calls mulk.

Rosenthal translates this word as “royal authority,” Isawii translates its as “sovereignty,” Baali uses “state,” and Goodman uses “kingdom.” Ibn Khadun notes that this kind of power was not the same kind most clan chieftains or nomadic leaders possess:

According to their nature, human beings need someone to act as a restraining influence and mediator in every social organization, in order to keep members from fighting with each other. That person must, by necessity, have superiority over the others in the matter of asabiyah…. Such superiority is royal authority (mulk). It is more than leadership. Leadership means being a chieftain, and the leader is obeyed, but he has no power to force others to accept his rulings. Royal authority means superiority and the power to rule by force.16

ibid., 284.

Such authority springs from asabiyah but it is not asabiyah. Asabiyah is a corporate possession, a shared loyalty or partisanship possessed by entire clans or peoples. Sovereignty, on the other hand, cannot be divided. It is possessed by one man and one man only. In the end it is to him, not to his clan or to his people, the kingdom belongs.

Ibn Khaldun makes the distinction between the two in the following terms:

It is difficult for them [Bedouins] to subordinate themselves to each other, because they are used to (no control) and because they are in a state of savagery. Their leader needs them mostly for the asabiyah that is necessary for the purposes of defense. He is, therefore, forced to rule them kindly and to avoid antagonizing them. Otherwise, he would have trouble with the group spirit, and such trouble would be his undoing and theirs. Royal leadership [mulk] and government, on the other hand, require the leader to exercise a restraining influence by force. If not, his leadership would not last. 17

ibid., 306. This accords with what modern anthropologists have learned about hierarchy and leadership in contemporary nomadic societies. See Philip Salzman, Pastoralists: Equality, Hierarchy, And The State(Boulder, Co: Westview Press, 2004)

Royal authority is impersonal. It is deliberate and planned. It is upheld by the realm of bureaucrats and officials; it is enforced by law and the force of arms. It is, in simplest terms, coercion used to bring peace to the ruler’s realm and ensure that the ruler’s will is done inside it.

As the power of royal authority increases the incentives his warriors, clansmen, and followers face begin to change:

First, as we have stated, the royal authority, by its very nature, must claim all glory for itself. As long as glory was the common property of the group, and all members of the group made an identical effort (to obtain glory), their aspirations to gain the upper hand over others and to defend their own possessions were expressed in exemplary unruliness and lack of restraint. They all aimed at fame. Therefore, they considered death encountered in pursuit of glory, sweet, and they preferred annihilation to the loss of it. Now, however, when one claims all glory for himself, he treats the others severely and holds them in check. Further, he excludes them from possessing property and appropriates it for himself. People become too lazy to care for fame. They become dispirited and come to love humbleness and servitude. 18

Ibn Khaldun, Muqaddimah, Vol I, 339.

This is the root of the ‘asabiyah cycle’ Khaldun is famous for. On it rests the rise and decline of empires and nations.

NOTE: Ibn Khaldun actually describes two cycles and they are not the same. One is the ‘four generations from rags to riches and back’ cycle, which he believes affects individual lines of the royal house. He does not equate this with the rise and fall of kingdoms themselves, suggesting that once generation four comes around and screws things up enough, the ruling dynasty’s kinsmen will depose him and put another member of the clan with more sense on the throne, starting that cycle over. The kingdom collapses when the dynasty’s kinsmen themselves are no longer willing to fight for the ruling line at all – in essence, when they (and everyone else) has lost their asabiyah for it. [see Rosenthal trans., vol I, p. 280 for more on this]. This broader cycle, in which asabiyah waxes and wanes, is the one that transforms barbarians into kings and nomads into emperors. It is important not to confuse these two).

Thus in Khaldun’s view, asabiyah is not permanent. Almost inevitably, it dwindles away. The process can take generations, but the reason is always the same: “They have lost the sweetness of fame and asabiyah, because they are dominated by force.” 19To use a rather rough analogy to make clear the point: a community may agree that it is a good and saintly thing to give alms to the poor. But once a government steps in and decides that they will tax the community in order to provide for the poor, the nature of the exchange changes. What was once a decision freely made in a spirit of charity becomes an act compelled by force, tolerated (at best!) or resented by the givers. The spirit gives way when a law is in place. The principle could be restated: law is the substitution of asabiyah with coercion.

That law ascends and asabiyah withers away is in the interest of the new monarch, for the egalitarian party spirit that leads to conquest does not exalt the ruler when the conquest is over. Khaldun sketches this process out in the following terms:

ibid., 374.

It should be known that, as we have stated, a ruler can achieve power only with the help of his people. They are his group and his helpers in his enterprise. He uses them to fight against those who revolt against his dynasty. It is they whom fills the administrative offices, whom he appoints as Wazirs and tax collectors. They help him to achieve superiority. They participate in the government. They share in all of his other important affairs.

This applies as long as the first stage of a dynasty lasts, as we have stated. With the approach of the second state, the ruler shows himself independent of his people, claims all the glory for himself, and pushes people away from him with the palms of his hands. As a result, his own people become, in fact, his enemies. In order to prevent them from participation (in power) the ruler needs other friends, not of his own kin, which he can use against his own people and who will be his friends in their place. These new friends become closer to him than anyone else. They deserve better than anyone else to be close to him and to be his followers, as well as to be preferred and to be given high positions, because they are willing to give their lives for him, preventing his own people from regaining the power that had been theirs and from occupying with him the rank to which they had not been used. 20

ibid., 372.

For the societies of the Middle East with which Ibn Khaldun was most familiar “new friends” could be of two types—the first were the civilized urbanites and advisers who were never part of the ruling clan but, possessing institutional knowledge and familiarity with the cities now ruled, prove useful to the ruling clan (their mandarin counterparts in traditional China, whose influence can be seen clearly in the Liao, Jin, Yuan, and Qing courts, are another excellent example of the type). The second are mercenaries – or as was the case in the medieval Middle East, slave armies. For Ibn Khaldun the reliance on slave armies and Turkic warriors by Arab dynasts was a sure sign of a dynasties’ decline, vivid proof that the clan in question no longer commanded the asabiyah needed to preserve itself. When only those compelled by punishment or induced by payment will fight in your name the end is near.

Part of the reason the ruling line loses this capacity is the corrupting nature of urban civilization itself:

By its nature, royal authority demands peace. When people grow used to being at peace and at ease, such ways, like any habit, become part of their nature and character. The new generations grow up in comfort, in a life of tranquility and ease. The old savagery is transformed. The ways of the desert which made them rulers, their violence, rapacity, skill at finding their way in the desert and traveling across wastes, are lost. They now differ from city folk only in their manner and dress. Gradually their prowess is lost, their vigor is eroded, their power undermined…. As men adopt each new luxury and refinement, sinking deeper and deeper into comfort, softness, and peace, they grow more and more estranged from the life of the desert and the desert toughness. They forget the bravery which was their defense. Finally, they come to rely for their protection on some armed force other than their own. 21

ibid., 372.

But the problem with urban civilization is not just that it makes me people soft. It also affects their conception of asabiyah. Goodman explains:

Sublimated ‘asabiyya, the “identification” of individuals with the group such that they effectively sub- ordinate their atomic interests not to one another, simpliciter, but to one another as office holders, as possessors of various special and general rights which arise in a diversified, money economy and a more or less peaceful, legalized civil society, is necessary qua social bond for the maintenance of such a society; but qua sublimated, it bears within it the seeds of its own destruction.

….In the tribe it does not much matter how one feels about one’s obligations; the painful and immediate consequences of dissociation from the group are all too evident and pressing. But in civilization obligations have proliferated and grown complex; multiple substitutions of doer and recipient are possible (for the relation, not the identity of its participants is what counts); a thick cushion against the consequences of neglect is provided by the built-up institutions of society itself; and above all, the rise of wealth, the products of industry, including leisure (which is at once the most precious and most dangerous product of human industry) have opened the door to the most convincing enemies of duty (for sublimated ‘asabiyya in the most general sense is duty), namely personal ease, personal safety, personal pleasure.” 22

Goodman, “Ibn Khaldun and Thucydides,” 261.

Asabiyah, then, amounts to the feeling among those dying that they are dying for their own. As soon as they begin to feel that they are not dying for their own, but are dying for the king, or for someone else’s clan, or for some obscure institution that is not them — well, that is when asabiyah is gone and the kingdom is in danger. Civilized life shrinks the asabiyah that once united people of different lineages, tribes, and occupations until the people of a kingdom only feel a sense of loyalty to themselves, of if you are lucky, those in their immediate neighborhood or caste. But at this point the feeling they have is not really asabiyah at all, but the narrow self interest Hobbes would appreciate. This leaves the kingdom open to attack from the next round of nomadic tribesmen united by charismatic leaders into one indivisible asabiyah driven force.

Although it was not his intent, I think Ibn Khaldun here answers another puzzle apparent to the careful observer of human affairs. It has oft been held that a strong enemy unites a divided people. When faced with with a foe that threatens liberty and the integrity of the realm, private disagreements ought to be put aside until victory has been declared. But it is not apparent that history actually works this way. If one must compare the rising and declining eras of history’s great empires–here I think of the Romans, the Abbasids, the Ming, the great empires of Castille and the Hapsburgs, or the Russian Empire of Tsarist fame (no doubt other examples can be found with if more thought were put to the question)–it does not seem the enemies they faced in their early days were any less powerful or cunning than the enemies that pushed them to extinction. The difference was in the empires themselves; where the wars of their birth forged nations strong and martial, the wars of their decline only opened and made raw violent internal divisions. Even destruction cannot unite a people who have lost all feeling of asabiyah.

|

| Andrea Cilesti, Tamerlane and Bayezid (c. 1770) Image Source |

The concept of asabiyah is applied most easily to the distant past. One cannot read histories of the early Islamic conquests and the slow hardening of state authority in Umayyad and Abbasid times without seeing Ibn Khaldun’s cycles within it. I have alluded to many examples of these same themes in East and Central Asian history, for I have found that his theories map well to state-formation among pastoral nomads across the world, including those places Ibn Khaldun had barely heard of. Indeed, Ibn Khaldun’s “independent science” can be applied to almost any pre-modern society or conflict without undue violence to his ideas. I recently wrote that in the pre-modern world, “internal cohesion and loyalty were often the deciding factor in the vast majority of military campaigns” 23 Ibn Khaldun provides a convincing explanation for where such cohesion came from and why it so often failed when kings and princes needed it most dearly.

There are several reasons why it is difficult to see the hand of asabiyah in the rise and decline of modern great powers. Military science has progressed in the centuries since Ibn Khaldun wrote the Muqaddimah; the drills and training seen in the militaries of our day are capable of creating a strong sense of solidarity and cohesion even when such feelings are absent in the populace at large. In that populace the nationalist fervor that accompanies mass politics has eclipsed (or perhaps, if we take asabiyah as the nucleus of nationalist feeling, perfected) asabiyah as the moving force of modern conflict. This sort of nationalism, dependent as it is on mass media and technologies unknown to Ibn Khaldun, has a dynamic of its own that he could not have foreseen.

T. Greer, “ISIS, The Mongols, and the ‘Return of Ancient Challenges,” The Scholar’s Stage (18 December 2014).

The most important difference between Ibn Khaldun’s world and our own, however, concern the fundamental structure of the societies in which we live. Ibn Khaldun’s was a static age where wealth was easier to seize than make. This is not the case today. For the past two centuries military power has been intertwined with economic growth and industrial capacity. No more can poor ‘Bedouins’ living beyond the pale of civilized society dethrone kings and reshape empires. In the more developed nations of the earth there is so little fear of war that both asabiyah and nationalism are sloughed off with few misgivings.

Despite all these differences, Ibn Khaldun did articulate principles that remain relevant despite their age. The first and most important of these is that social cohesion should be understood as a vital element of national power. Wars are rarely won and strategies rarely made without it. A nation need not be engaged in existential conflict to benefit from strong asabiyah. Absent solidarity, internal controversies absorb the attention of statesmen and internal divisions derail all attempts to craft coherent policy. Strategic malaise is one byproduct of a community deficient in asabiyah.

Ibn Khaldun offers few cures for this sorry state. He asserts instead that asabiyah is not and never will be an artificial invention. The fragility of despotic regimes maintained by blood and fear reflect this fact. No matter how dearly the despot may wish it, the most powerful forms of human cooperation cannot be produced by coercion. Indeed, the most powerful forms of cooperation cannot be produced at all. Ibn Khaldun’s vision is pessimistic: great men may ride the waves of history but they cannot direct their force. Asabiyah will rise and fall as communities grow and then splinter, bureaucracies expand and then calcify, and laws are established but then too quickly multiply. What was constructed for the glory of a people in past ages only hampers their progress and hastens their decline in the present. All the good man can do in such a time of decline is wait for the old order to fall apart and join the asabiyah driven group of men and women ready to rebuild upon the ashes.

An excellent post, particular for the May Day long weekend! Ibn Khaldun is on my to-read list, but it is a long list.

The only thing I would suggest was that states often fall to much =less= formidable foes than they faced in their prime. Alexander fighting the Persians had to overcome the sort of five-fold or ten-fold inferiority of resources that Cyrus had faced against Croesus and Nabonidus, but in both cases the upstarts from the edge of the known word triumphed over the people at the centre.

Hi Mr Greer,

I am a student from East Asia in a US Institution now as an undergraduate. I really appreciate your posts; its incredible that someone who understands east asia so 'thickly' even exists here in the US.

Do you think multiculturalism and its associated challenges might be an echo of the cycle of asabiya in Western Societies today? After all, Michael Houellebecq's Soumission capitalises on the fact that a society can be taken over with sufficient ease not when the outsiders have greater numbers, but eralier than that. It is sufficient for the outsiders to have greater internal solidarity than the insiders do; if they are more willing to disregard the bureaucratic rules that circumscribe acceptable political behaviour and are more willing to die for their cause.

@anon-

I thank you for your compliments.

My understanding of Michael Houellebecq is completely based on popular treatments in magazines and newspapers, especially this essay in the New York Review of Books by Mark Lilla. Lilla concludes with this stunning paragraph:

For all Houellebecq’s knowingness about contemporary culture—the way we love, the way we work, the way we die—the focus in his novels is always on the historical longue durée. He appears genuinely to believe that France has, regrettably and irretrievably, lost its sense of self, but not because of immigration or the European Union or globalization. Those are just symptoms of a crisis that was set off two centuries ago when Europeans made a wager on history: that the more they extended human freedom, the happier they would be. For him, that wager has been lost. And so the continent is adrift and susceptible to a much older temptation, to submit to those claiming to speak for God. Who remains as remote and as silent as ever.

I am a bit divided on whether or not the crisis of multiculturalism in Europe is tagged to the short asabiyah cycle in Europe or to the much longer term crises Hollendocq sees. I certainly don't think multi-culturalism itself is the problem; you are from East Asia, so you know that there were plenty of mult-culti dynasties in Chinese history (the Tang, Yuan, and Qing come to mind) that were the stronger for it… in the beginning at least.

Western Europe is actually a very interesting case study, because it was here that the asabiyah cycle was first broken. It was also here that its modern replacements–nationalism and the propaganda that makes it possible first arose and were then perfected as instruments of state control. Europeans were to reject these instruments after two world wars in which they were prominently showcased left them in desolate ruins.

Europe has climbed away from asaboyah dynamics, rejected modern nationalism… and have been left empty and brittle. Luckily, we live in an age where the empty and brittle will not be destroyed by barbarian swarms from without.

I think the history of modern nationalism proves that asabiyah CAN be generated artificially. In the hands of truly ruthless and skilled practicioners, it can generate suicidal devotion on the part of followers (the particular case of Meiji and Showa era Japan is one of the bloodiest examples – where a caste-based, divided aristocracy transformed itself into a military dictatorship, and where the children of disenfranchised peasants embraced the largely ahistorical values of their ruling class in the service of a country which had never been united).

Is there any real genuine evidence that Europeans are "empty and brittle" – other than enjoying peace and prosperity that are unprecedented in history? Also, that they have rejected modern nationalism? The fragility of the EU project in the face of real opposition seems to indicate that quite the opposite is true.

Asabiyah sounds too much like neuro/psychiatry. Asab- refers to mentality/psyche/spirit, while ashab(as—hub) refers to friends/associates.

"Military science has progressed in the centuries since Ibn Khaldun wrote the Muqaddimah; the drills and training seen in the militaries of our day are capable of creating a strong sense of solidarity and cohesion even when such feelings are absent in the populace at large."

The problem here is that a nation at peace, or only involved in small wars, will generally have a small military. If it faces an existential threat, without asabiyah, it will have a hard time raising enough military to defend itself.